January 2020

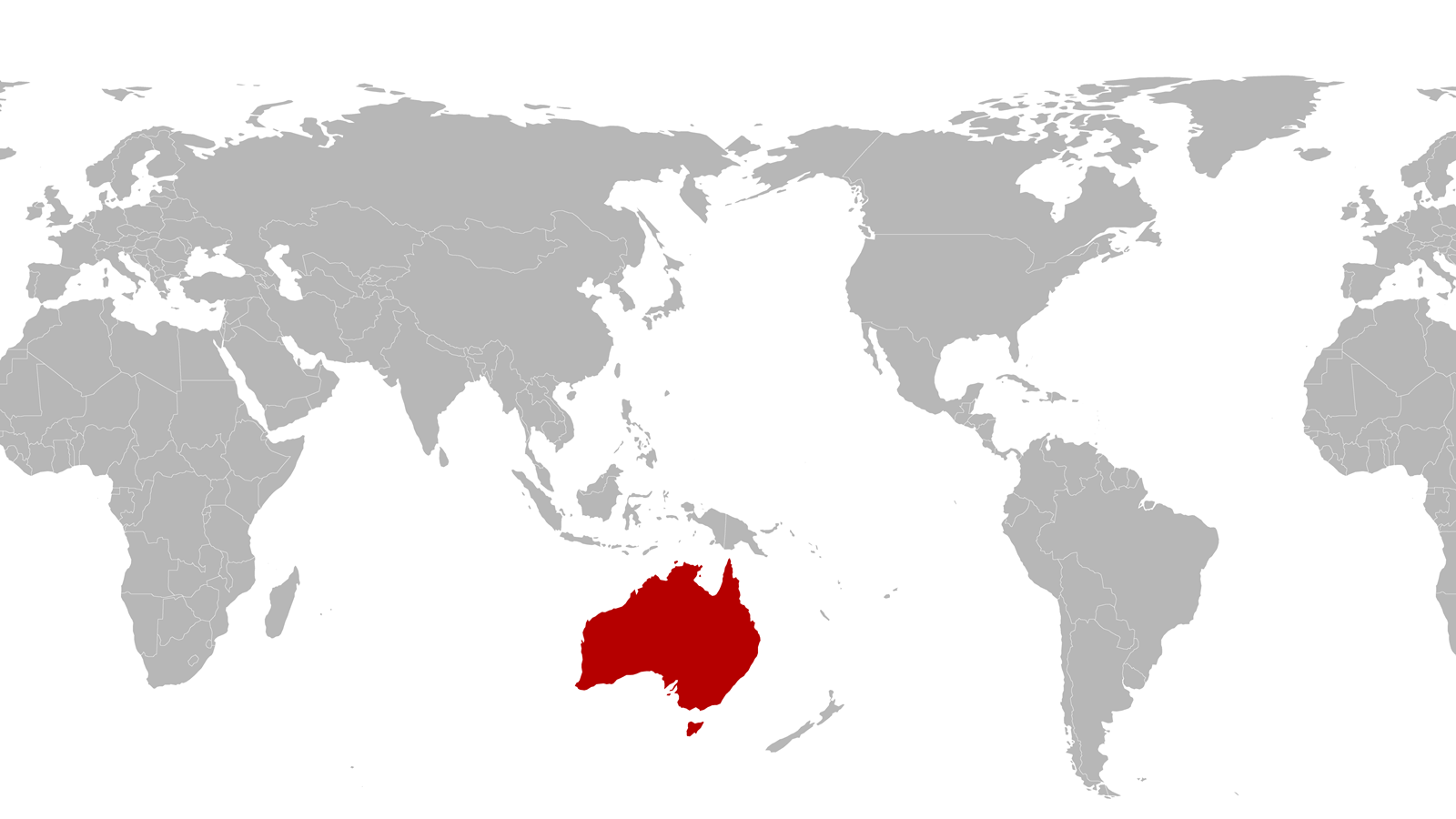

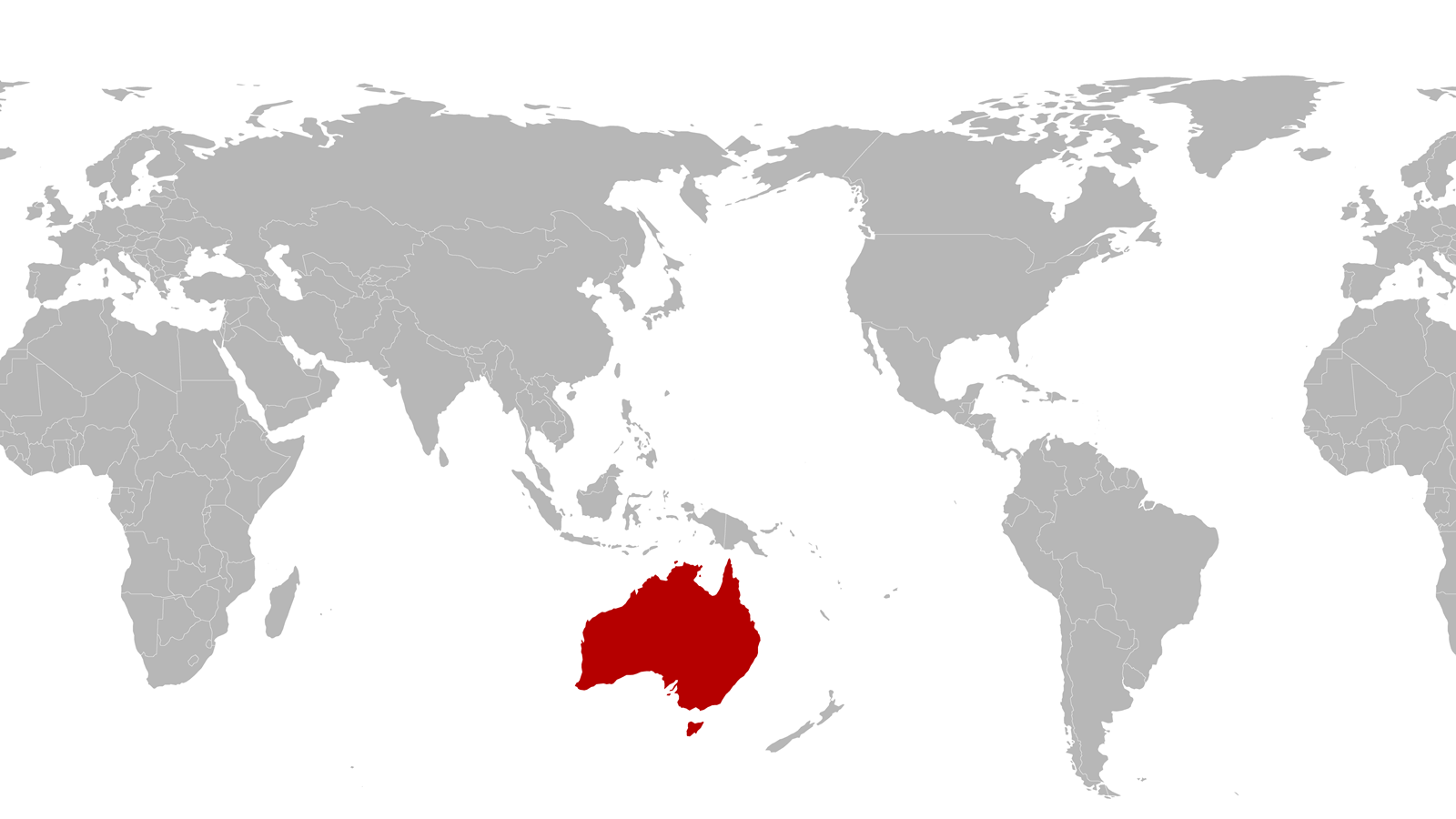

In Australia, Trent Munro is getting ready to host a house party when he receives ‘a cryptic request for a call’.

The call comes at 9pm.

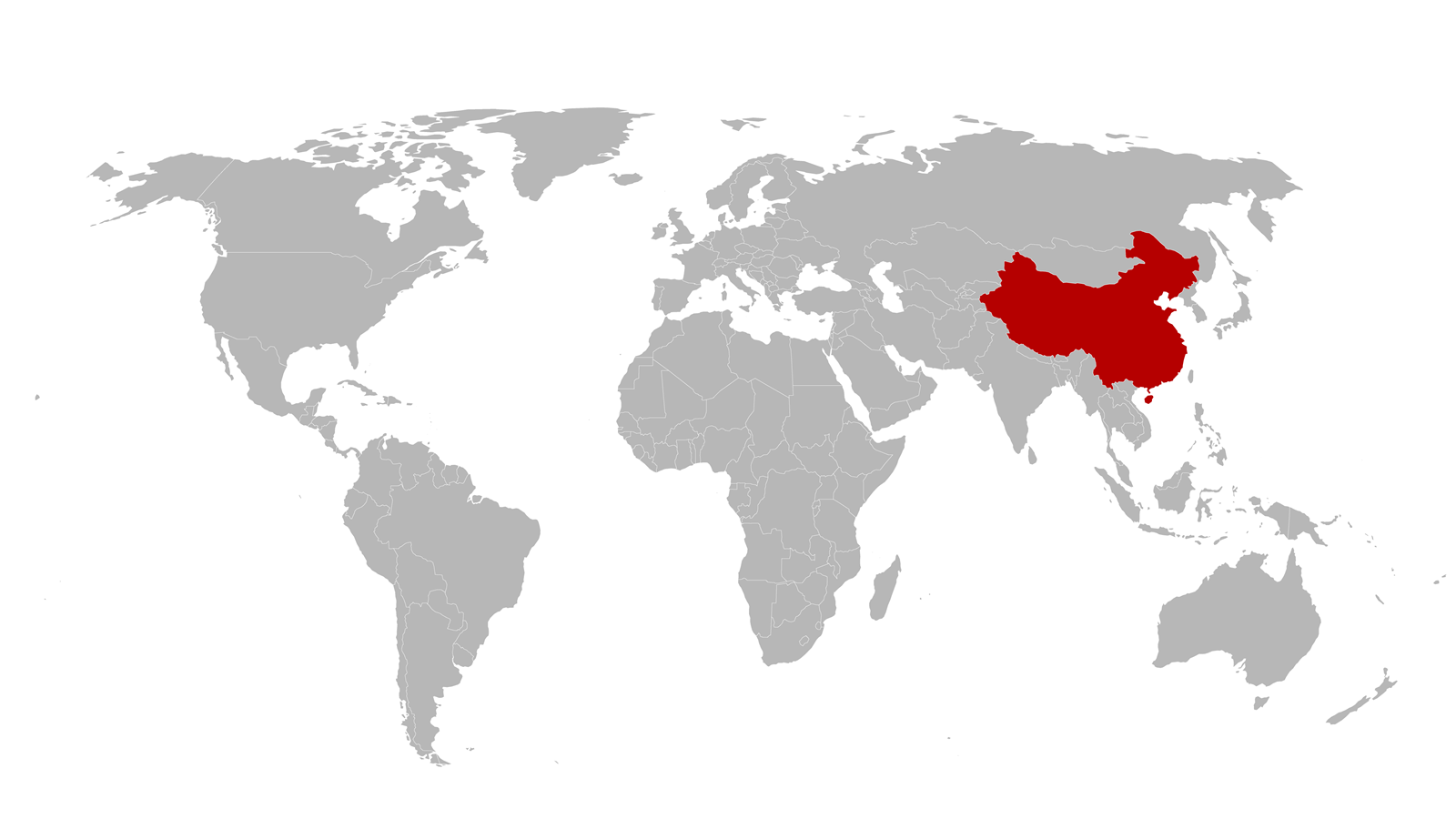

His friends chat and laugh in the background, but Munro is silent as he listens to members of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations discuss news coming from China.

They tell him it’s ‘going to be a big deal’.

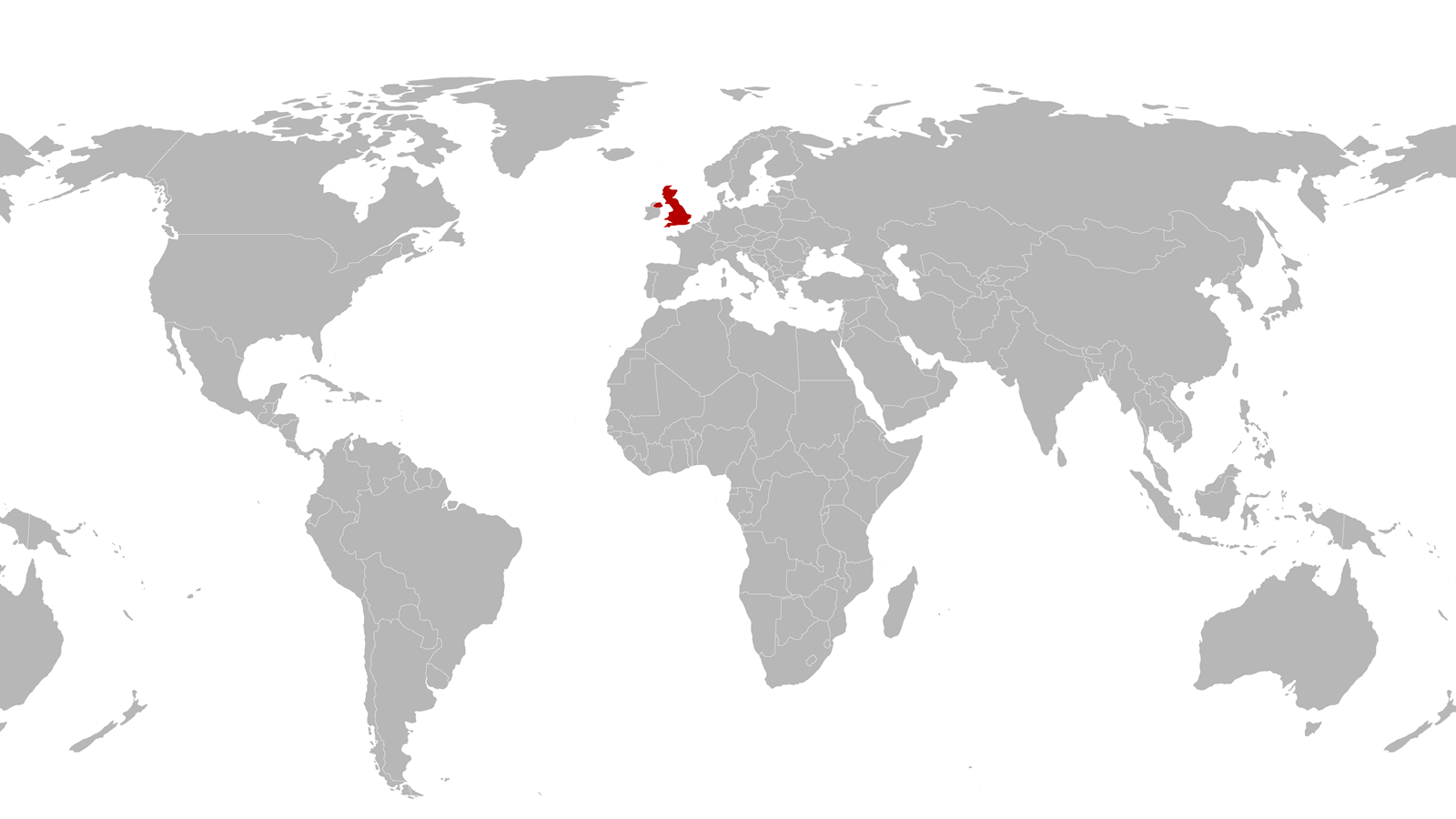

At Imperial College London, UK, vaccine researcher Anna Blakney’s boss Robin Shattock suggests working on a vaccine against a new virus.

She declines – it’s a distraction from their other work.

‘I talked him out of it,’ she says.

‘But luckily, he didn’t give up.’

In China, staff at the offices of speciality chemicals company Croda International are sent home, not knowing when they will return.

Millions of containers, including Croda’s raw materials, will lie stranded in Chinese ports for weeks.

Amadou Sall, the director of the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, Senegal, calls Joe Fitchett, the medical director of diagnostics company Mologic in Bedford, UK.

Sall tells him ‘We need to do something for Africa before this gets out of hand.’

January 2020

In Australia, Trent Munro is getting ready to host a house party when he receives ‘a cryptic request for a call’.

The call comes at 9pm.

His friends chat and laugh in the background, but Munro is silent as he listen to members of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations discuss news coming from China.

They tell him it’s ‘going to be a big deal’.

At Imperial College London, UK, vaccine researcher Anna Blakney’s boss Robin Shattock suggests working on a vaccine against a new virus.

She declines – it’s a distraction from their other work.

‘I talked him out of it,’ she says.

‘But luckily, he didn’t give up.’

In China, staff at the offices of speciality chemicals company Croda International are sent home, not knowing when they will return.

Millions of containers, including Croda’s raw materials, will lie stranded in Chinese ports for weeks.

Amadou Sall, the director of the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, Senegal, calls Joe Fitchett, the medical director of diagnostics company Mologic in Bedford, UK.

Sall tells him ‘We need to do something for Africa before this gets out of hand.’

Almost a year on from these opening moments of the global coronavirus pandemic, the virus is still playing havoc with our lives. But chemistry has helped steer us through the crisis. Testing labs have quickly mobilised to help tell whether the virus has entered our bodies or not. Chemical producers have rapidly adapted to keep making the materials we need to protect ourselves. Research chemists have changed direction to add to the pool of knowledge about our insidious enemy. Meanwhile, vaccine and drug developers have sought treatments to protect the world – efforts that may finally set us on a road to normality.

It’s apt that the virus that has ruled the world this year is named after its crown, or corona. Vaccine researchers focus on the protein that forms the crown-like spikes protruding from a bubble of oily lipid molecules that forms the virus’s outer coat. We’ve already faced epidemic coronaviruses with this structure, including the one that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) in 2003, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) in 2012.

Trent Munrohas various senior roles at the University of Queensland (UQ), Australia, including programme director for the CEPI-funded Vaccine Rapid Response pipeline. Following the call from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), his team could swing into action on the new virus because Chinese researchers had published the sequence of the as-then-unnamed coronavirus’s DNA genetic material on 7 January. His colleagues had already started a mock response and had ordered the RNA from a commercial supplier to start vaccine development.

The Queensland team had previously worked on Mers, whose spike proteins attach to cells in our airway that produce a protein called ACE2. The oily bubble fuses with these cells’ outer membranes. The virus can then release its RNA, putting the cell under its control. The cell translates the instructions to make new virus copies that spread through our bodies, and from there to other people. We might have been looking at an even longer crisis if the new virus had not been so similar to Mers. The researchers studying that coronavirus had developed vaccines based on the spike proteins. ‘To get a really robust immune response, the spike protein needs to be held in a form as it would normally be on the surface of the virus,’ Munro says. But simply chemically synthesising the spike protein doesn’t give it the shape needed.

The Queensland researchers – including Munro’s colleaguesPaul YoungandKeith Chapel– have therefore developed a protein subunit vaccine, replacing part of the spike that normally goes through the lipid membrane. ‘We add on a series of amino acids called a clamp, derived from another viral protein, and it’s very stable,’ Munro says. Most other vaccine candidates also exploit the spike protein to get the body to mount an immune response. But they shape it by replacing some of its amino acid building blocks with proline amino acids that twist the protein chain, Munro explains. As the Queensland team worked on transferring the clamp approach to the new virus, the World Health Organisation (WHO) named it Sars-CoV-2 in February, and the disease it causes Covid-19.

Working through lockdown

Anna Blakney’s team at Imperial College London in the UK raises immune responses using sections of the virus’s RNA, rather than protein subunits. Like Sars-CoV-2, they use our cells to make proteins that raise the immune response – but the Imperial team don’t make the entire virus. Vaccine frontrunners like US biotech company Moderna and the partnership between US pharma giant Pfizer and BioNTech, a German biotech company, also exploit RNA-based approaches.

Take care of yourself, do what you can, and try to take care of the customers

‘It’s so much faster to make in the first instance, but also to produce at large scale,’ explains Blakney. That will be valuable if a new mutation emerges, she stresses. Striving to realise such concepts keeps vaccine researchers like Blakney and Munro in their labs, even as Covid-19 has plunged many of us into isolation and working from home.

After Croda staff in China switched to home working in January, explainsNicolas Gedda, managing director for the company’s Western Europe sales operations, the company quickly put crisis management plans in place. ‘It was “Take care of yourself, do what you can, and try to take care of the customers” in that order,’ he says.

Even as it made this transition, Croda kept supplying its customers, especially those making personal protective equipment (PPE) and cleaning products. Croda supplies glycerine, a key ingredient in hand sanitisers. At first, Croda donated glycerine stock to many of its European customers, Gedda says, but quickly realised that it could easily make sanitiser lotions itself, and donate them where needed. Then it started to donate its stocks of PPE, in what has now become a programme called Acts of Kindness, where each Croda sites grant money to help its local community.

The chemicals industry has seen steep declines in demand from house builders and carmakers, Gedda observes. Greater demand from other industries making cleaning products and plastic packaging has partly offset this, he adds, but not completely. Even personal care – products like perfume and lipstick – struggled ‘for the first time in history’. ‘The fact that duty free and beauty stores were closed is unprecedented,’ Gedda says.

The pandemic looks set to transform the industry, with some companies changing suppliers to avoid problems faced in shipping materials from afar in future, Gedda continues. There will be more home working and less business travel to visit customers in future, with video conferencing having proven its worth, he says. ‘Pre-pandemic we were a bit reluctant to allow some departments to be working from home,’ Gedda reveals. ‘The pandemic is shifting the balance.’

March 2020

The petrochemical company Braskem considers shuttering its sites in the US towns of Marcus Hook and Neal as the pandemic reaches North America.

Yet its products are vital for making sanitary wipes, hospital masks, gowns and hoods.

The staff choose to live on site for 30 days.

Katriona Methven, senior director of international regulatory affairs for Gilead Health in UK and Ireland, is working every weekend and sometimes 12–14 hours a day.

Gilead’s antiviral drug remdesivir may have the potential to help patients with severe cases of Covid-19.

‘I’d get phone calls at three o’clock in the morning signing off compassionate use requests for people that were critically ill and their physician thought this was their only hope,’ Methven says.

‘I was absolutely terrified.’

Liliana Quintanar Vera’s plans are in ruins.

Her team at Cinvestav research institute in Mexico City, Mexico, had been due to go to the Stanford synchrotron. The trip is cancelled due to Covid-19.

Her team starts working on how the virus interacts with a zinc-dependent enzyme.

‘It’s not as important as the vaccine,’ Quintanar says. ‘But it’s our way of contributing.’

March 2020

The petrochemical company Braskem considers shuttering its sites in the US towns of Marcus Hook and Neal as the pandemic reaches North America.

Yet its products are vital for making sanitary wipes, hospital masks, gowns and hoods.

The staff choose to live on site for 30 days.

Katriona Methven, senior director of international regulatory affairs for Gilead Health in UK and Ireland, is working every weekend and sometimes 12–14 hours a day.

Gilead’s antiviral drug remdesivir may have the potential to help patients with severe cases of Covid-19.

‘I’d get phone calls at three o’clock in the morning signing off compassionate use requests for people that were critically ill and their physician thought this was their only hope,’ Methven says.

‘I was absolutely terrified.’

Liliana Quintanar Vera’s plans are in ruins.

Her team at Cinvestav research institute in Mexico City, Mexico, had been due to go to the Stanford synchrotron. The trip is cancelled due to Covid-19.

Her team starts working on how the virus interacts with a zinc-dependent enzyme.

‘It’s not as important as the vaccine,’ Quintanar says. ‘But it’s our way of contributing.’

Brazilian petrochemical company Braskem closed its North American offices on March 16, saysMark Nikolich, chief executive of Braskem America. Prioritising worker and community safety over revenue, Nikolich and his executive colleagues considered ‘temporarily idling’ their polypropylene production sites but delegated the decisions to local site leadership teams. In the towns of Marcus Hook and Neal, Braskem staff recognised that their products were vital in making sanitary wipes, hospital masks, gowns and hoods. They therefore made the remarkable decision to live on site for 30 days.

The team members voluntarily came up with the idea, being concerned about coming back and forth to the site, Nikolich explains. ‘We ended up with more volunteers than we needed to operate the plants,’ he says. ‘Both plants ran without any cases for the entire 30 day period. They were able to make about 140% of the normal demand for the medical and hygiene market. Back then, we thought that was huge. We didn’t know that months later, we’d still be in a pandemic.’ Nikolich is therefore concerned about Covid-19 fatigue ultimately lowering people’s vigilance. But since the live-ins, Braskem America is still working with operations-critical staffing and using new shift schedules designed to minimise transmission. This has improved safety ‘because we have less complexity at the plant, there are fewer people’.

Nikolich sees the pandemic as a chance for ‘old industrial businesses to fundamentally change’. He wants to advance diversity and inclusion programmes, enhance home working culture and cut activities like unnecessary business travel, citing the 300,000 air miles per year he previously travelled. ‘How much of that was really necessary?’ he asks. ‘Industrial businesses in the US look very male and very white. Attracting and retaining today’s best talent is a challenge. This has given us an opportunity to progress our work environment to make our businesses more receptive to a more diverse group of potential team members.’

Gilead Sciences, developer of antiviral drug remdesivir, also promptly moved to home working where possible, explainsKatriona Methven国际监管affa高级主管irs for UK and Ireland. Previously studied in Ebola virus outbreaks, remdesivir stops viral RNA reproduction. Its potential to fight Covid-19 soon gained attention, demanding action from Gilead and regulators like the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Authority (MHRA). Yet prosaic obstacles, like Gilead using Zoom as its virtual meeting platform while MHRA could only use Microsoft Teams, proved surprisingly challenging. Methven also has impaired hearing, meaning some common practices of the ‘new normal’ cause her problems. ‘When people have got masks on I can’t read their lips,’ she says. ‘Zoom meetings are almost as bad when people refuse to turn their cameras on.’

As remdesivir hadn’t been approved for marketing, the only way people could initially access it was through compassionate use requests. Approving such requests in the UK is Methven’s responsibility. ‘From March until July I probably worked all weekend and some 12–14 hour days,’ she says. ‘I’d get phone calls at three o’clock in the morning signing off compassionate use requests for people that were critically ill and their physician thought this was their only hope. I was absolutely terrified. If I slept through that phone call, then the drug wouldn’t ship from the US in that day. I could personally have contributed to somebody’s demise.’

Drug dilemmas

To manage the unprecedented demand, Gilead moved from compassionate use to programmes like the UK’s Early Access to Medicines Scheme. Methven’s life finally calmed down slightly in July when remdesivir got conditional approval for marketing in Europe under the brand name Veklury. ‘Within six months, it went from being a phase 2b medicine to having a licence,’ Methven observes. ‘We had 14,000 units of remdesivir available at the start of the year. By the end of the year, we’re manufacturing millions of units. That is totally unprecedented.’

Even with that demand, remdesivir’s benefits have come under question.The WHO recommended against its use in Covid-19 patients on 20 November, saying there wasn’t enough evidence that it improves survival or improves other outcomes, while supporting further trials. Yet Gilead disputes this finding, saying in a statement that it is ‘concerned that the WHO continues to refuse to provide the underlying data sets for these guidelines’.

As isolation measures came in, chemists likeLiliana Quintanar Vera在墨西哥城Cinvestav研究所, Mexico, couldn’t do their experiments. Quintanar’s team had been due to go to the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource in the US in March. Quintanar’s team studies how metal ions like copper and zinc interact with proteins using x-ray absorption spectroscopy. But at the last minute, the trip was cancelled due to Covid-19. ‘We were so excited, because we had a couple of weeks at two different beam lines,’ Quintanar says. ‘It was really disappointing.’

Yet the pandemic has brought opportunities too, with special calls from synchrotrons for research related to Covid-19. The ACE2 protein that the virus exploits to enter our cells is a zinc-dependent enzyme, and so it suits Quintanar’s expertise perfectly. She wants to know whether the virus’s interaction with ACE2 – and targeting it with drugs – might impact the protein’s important role in our body. The Cinvestav researchers have already sent protein samples to the Swiss Light Source. ‘It’s not as important as the vaccine, but it’s our way of contributing,’ Quintanar says.

Zinc has already featured prominently in Covid-19 drug treatments, sometimes being paired with hydroxychloroquine. On March 28, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved hydroxychloroquine for emergency use against Covid-19. Yet by 15 June the FDA had revoked that authorisation, based on studies that it showed no benefit. However Quintanar’s colleague Fanis Missirlis studies metal transport inDrosophilafruit flies. Missirlis is now studying whether zinc could have been the most beneficial component. ‘There are reports saying that patients with zinc deficiency are doing much worse,’ says Quintanar.

与此同时,Quintanar继续教学,亲密关系g online classes. She is looking forward to using such classes to gain more balance in her life, minimising her long commute across Mexico City. ‘The activation barrier to do things online has gone down,’ she stresses. Yet the flipside of this is that she has taken on even more domestic responsibility, and is concerned that the pandemic may have an uneven impact on female scientists.

Quintanar has other background worries. Through October she protested once a week against science funding reforms in Mexico. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has also downplayed the pandemic, disregarded the use of masks and attacked scientists. Finally, Quintanar notes that Mexicans share a further concern with many other countries: Will there be enough vaccine for everyone?

November 2020

Amadou Sall has done something for Africa.

In Senegal, a facility set up by the Institut Pasteur Dakar to make lateral flow immunoassay rapid tests for Covid-19 is inaugurated.

‘You have expertise locally and it becomes much more affordable,’ says Sall. ‘We’re trying to show that we can improve the whole health system.’

Anna Blakney sits on a task force seeking to ensure the UK has sufficient capacity for RNA vaccines.

Her team has spun out a company so that its vaccines are ‘available all over the world to both developing and developed countries’.

November 2020

Amadou Sall has done something for Africa.

In Senegal, a facility set up by the Institut Pasteur Dakar to make lateral flow immunoassay rapid tests for Covid-19 is inaugurated.

‘You have expertise locally and it becomes much more affordable,’ says Sall. ‘We’re trying to show that we can improve the whole health system.’

Anna Blakney sits on a task force seeking to ensure the UK has sufficient capacity for RNA vaccines.

Her team has spun out a company so that its vaccines are ‘available all over the world to both developing and developed countries’.

Back in January, whenAmadou Sall, the director of the Institut Pasteur in Dakar, Senegal, spoke toJoe Fitchett, medical director at Mologic in Bedford, UK, Sall mentioned that his group needed molecular diagnostic kits for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests that have been the main tool to identify Covid-19. ‘That was really profound now in hindsight, because many of the companies just wouldn’t make their kits available,’ Fitchett says.

Part of the solution was exploiting a factory in Dakar to produce rapid pregnancy test-style lateral flow immunoassays (LFIAs) for viruses common in Africa. The 30-person, 300m2facility, called diaTROPiX, was already being set up by the Institut Pasteur Dakar, Mologic and four other partners (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, The Mérieux Foundation and bioMérieux in France and the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics in Switzerland).

Usually less sensitive and specific but quicker than PCR tests, LFIAs are useful to know how much virus is circulating and finding asymptomatic cases, explains Sall. Making the tests in Senegal at the facility, inaugurated in November, brings many benefits, he adds. ‘You have expertise locally and it becomes much more affordable,’ Sall explains. ‘It’s also very important as a showcase that Africa can handle innovative products and international partnerships to fight important diseases. And diagnostics is usually the point of entry for the health system, so by doing this we’re trying to show that we can improve the whole health system.’

To help with the Covid-19 crisis, Mologic developed two different types of LFIA. One test puts proteins that recognise three human antibodies – immunoglobulins A, M and G (IgA, IgM and IgG) – on a nitrocellulose strip, on which medical staff can put a blood droplet. If the blood contains antibodies against coronavirus proteins, these antibodies will bind to the strip and a red coloured marker, producing red lines. The other Mologic test recognises antigens in a similar way, based on specific coronavirus protein targets, starting either from saliva or a throat swab.

‘We can detect very low levels of protein compared to others,’ says Fitchett. ‘But what’s novel about this is making sure it’s manufactured for the first time in Africa. We’re making it delinked from commercial return. We said from the beginning if you profiteer from the pandemic, we only prolong it.’ Fitchett says that the partnership will now look at creating improved supply of PCR lab reagents to complement the LFIA devices for future pandemics. Yet Fitchett is impressed by the response to the pandemic in many countries in Africa, which have been less hard-hit than those in other continents.

Preparing for the next pandemic

萨尔解释说,这是原因之一population is younger on average, with Covid-19 hitting older people harder. Genetic and climate factors have also been suggested as reasons, but Sall says that more evidence is needed to support these hypotheses. He also notes that Covid-19 reached Africa later than the other continents, giving its countries more time to prepare. But the countries also have more experience. ‘Africa has around 120 epidemics every year and these have helped a lot in rehearsing,’ Sall says. ‘Capacity has been developed for that, particularly for Ebola in 2014 and 2016.’

访问Covi所需措施的问题d-19 even affects a rich country with relatively low virus levels like Australia, adds Munro. Like other countries, its government has pre-purchased millions of doses of the different vaccine candidates. Yet even Australia doesn’t know where it is in the queue for these orders. Munro therefore stresses the role of CEPI in helping enable equitable global access, building on the Queensland team’s partnership with CSL Seqirus, who will make the final vaccine at its Melbourne site. A proportion of all of the doses from CEPI funded programs will go into theCOVAXinitiative that aims to make vaccines available to lower income nations.

A variety of options may be needed to live with Covid-19 in years to come, Munro adds. ‘Unless something changes it seems highly likely that this virus will be circulating for a long period of time,’ he says. But as this article went to press,UQ and partners CSL announcedthat, in spite of a robust response to the virus and a good safety profile, they would not progress the vaccine beyond its phase 1 trial. Initial data suggest that trial participants generated antibodies that would interfere with HIV tests, producing false positives.

The UK also has vaccine manufacturing concerns, says Blakney, who sits on a task force seeking to ensure the country has sufficient capacity for RNA vaccines. She highlights the Vaccines Manufacturing & Innovation Centre in Oxford, which has already had approval to make Covid-19 products from MHRA. To deal with the international availability question, the Imperial team has spun out a company called VaxEquity to use the team’s saRNA technology and to ‘have it be available all over the world to both developing and developed countries’, Blakney says.

的Imperial trials are also behind the front-running vaccines, due to changes to their protocols and getting proper validation of the saRNA approach, adds Blakney. She wonders whether the pressing need might see a broader rethink of how vaccines get approved. For example, could a vaccine be distributed after proving safety in phase I trials? The risks include previously unanticipated side effects, and complacency from people given vaccines that may not work. ‘But if you distribute to everybody and it does work, then you’ve probably severely altered the trajectory of your economy,’ Blakney says. Such an idea reflects her desire to help the world learn from ‘how we responded to this pandemic, and set ourselves up to respond even better to the next one. We know that this isn’t going to be the last pandemic that we’ll ever have.’

Andy Extance is a science writer based in Exeter, UK

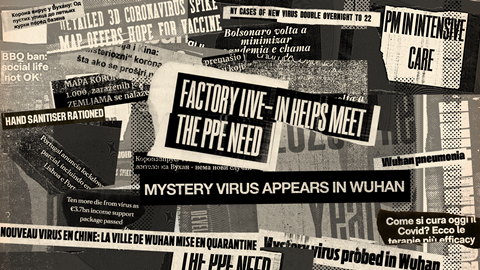

All headline images © Jimmy Turrel @ Heart Agency. Text for headlines taken from Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland, Le Monde, Corriere Della Sella, Exame, The Times, Staten Island Advance, CNN, O Globo, The Australian, Blic, BBC News (including Serbian language service)

No comments yet